- Join the Innovation Journey

- Our Platforms

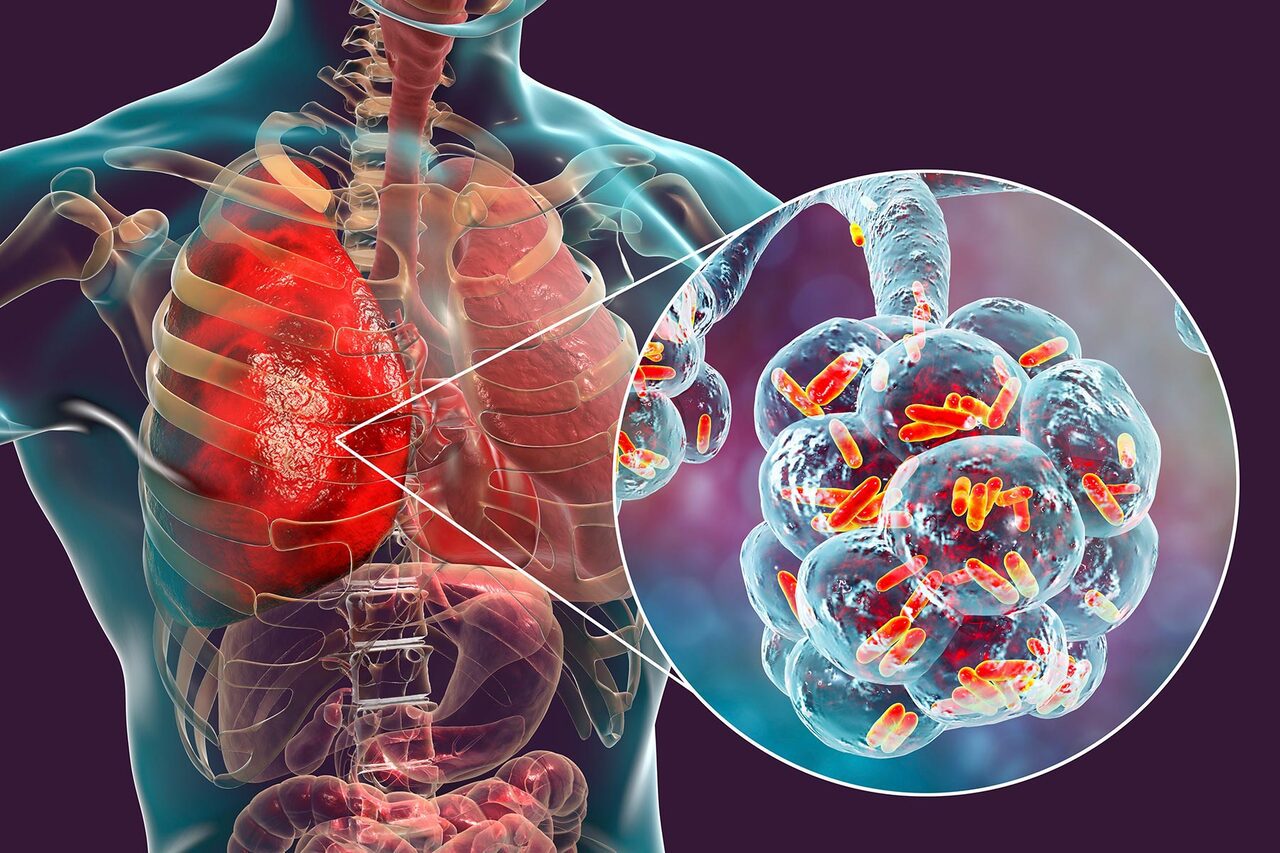

Tackling antibiotic resistance when treating pneumonia

New research has been published that identifies positive steps towards a better understanding of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), specifically in hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP).

Antimicrobial, or antibiotic resistance, is a growing global issue, yet little is known about how to dose antibiotics to minimise bacteria developing resistance in patients. However, the University of Liverpool is playing a key role in contributing to international efforts to better understand AMR.

This pioneering research is being delivered through iiCON’s AMR Modelling Platform, which is led by the University of Liverpool as a core consortium partner.

In a paper published this month, Dr Christopher Darlow, from the Antimicrobial Pharmacology & Therapeutics (APT) group at the University of Liverpool details a new experimental animal model of HAP. The model tests both the effect of meropenem – a commonly used antibiotic for HAP – and crucially determines how resistance to meropenem emerges.

Infections of the lungs are quite common in hospitals, with HAP accounting for approximately 10% of deaths in hospital. Because of the types of bacteria causing HAP and the large numbers of bacteria in the lungs during HAP, development of resistance to administered antibiotics to treat it is common. This is partly because doses of antibiotics are determined by drug developers to treat HAP effectively, but without consideration to the dose needed to prevent resistance emerging.

The team at the APT group, including Dr Darlow, have developed a new experimental model of HAP and used it to test the effects of meropenem. This model has allowed the team to detect both the amount of bacteria in the lungs as the antibiotic is given (i.e. is the antibiotic working to treat the infection) and also to detect the emergence of resistance, including by measuring the mutations in the genes of the bacteria that drive this.

In this work, the team demonstrated that too low doses of meropenem do treat HAP, but also cause a greater emergence of resistance. Conversely, resistance can be reduced by increasing the meropenem dose or by giving a second type of antibiotic (amikacin) at the same time. Both strategies may be used in clinical settings to reduce antimicrobial resistance. The team also mapped how the bacteria mutates and adapts to develop this resistance, giving insight into the underlying mechanisms.

Dr Christopher Darlow said: “Through this work we have highlighted the problem of resistance development in HAP when treated by meropenem and demonstrated potential strategies to prevent this i.e. increasing the meropenem or using a second antibiotic in combination. Beyond the implications for HAP, this is also a new experimental platform to allow antibiotics (both new and old) to be assessed for their ability to cause development of resistance and identify strategies to mitigate against this. We hope to use this platform for other antibiotics in the future to improve the use of antibiotics and prevent antibiotic resistance development.”

The paper, ‘Molecular pharmacodynamics of meropenem for nosocomial pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa’ was published in mBio (DOI:10.1128/mbio.03165-23).